Elston Howard had a distinguished career with the New York Yankees calling pitches and crushing the ball. While playing for the Yanks, he was an outstanding all-around catcher and helped them win critical games.

Howard was born in St. Louis, Missouri in February 1929. He was an elite athlete at Vashon High School. When he was 19 years old he turned down college football scholarships from three Big Ten powerhouses, the University of Illinois, the University of Michigan, and Michigan State University.

Ellie’s true passion as a young man was baseball. He rejected the football scholarship offers he received and, instead, signed to play professional baseball with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League. He roomed with Ernie Banks in 1950 and played outfield for three seasons with the Monarchs.

Seeing a lot of potential, the Bronx Bombers signed Howard in July 1950. The Yanks assigned him to the Muskegon Clippers, the team’s farm team in the Central League. Ellie missed the next two seasons due to his military service in the Army.

In 1953, he played for the Kansas City Blues of the Class AAA American Association. The next year the Yankees invited Howard to spring training and converted him into a catcher to back up the great Yogi Berra.

He played in the Class AAA International League in 1954. He performed extremely well and was chosen MVP of the league. The Yanks instructed Bill Dickey to work with Howard to perfect his catching skills and technique.

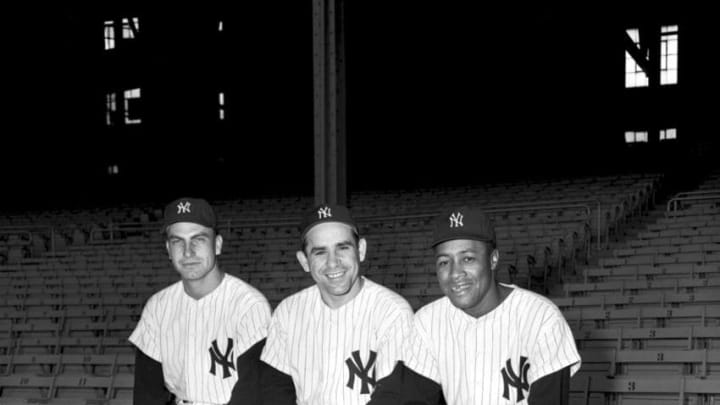

Ellie made the Yankees’ roster in 1955 and entered the second game of the regular season as a left fielder, the first time a black player had donned the pinstripes in the major league. As an unfortunate sign of the times, manager Casey Stengel called him “Eightball.” Stengel employed Ellie as a backup catcher and occasional outfielder. He hit .290 with 10 home runs and 43 RBIs during his first season with the club.

Backing up Berra for a few years during his prime prevented him from having more opportunities to shine, and the situation certainly depressed his numbers. If this was to occur today, Howard would be able to declare for free agency, join another team, and start behind the plate. This is exactly what Austin Romine chose to do during the offseason by signing with the Detroit Tigers. Free agency did not exist during the time Ellie played and was therefore not an option.